Vera and Donald Blinken Open Society Archives

What We Read: Pandemic Edition

Regularly updated! Articles, interviews, and podcasts on the coronavirus pandemic, recommended by the Blinken OSA staff.

Medical Anthropology / Christos Lynteris: Plague Masks: The Visual Emergence of Anti-Epidemic Personal Protection Equipment

(Photo: "Wearing anti-plague masks, front and side views," Manchurian Plague Prevention Service. / Taylor & Francis Online / The University of Hong Kong Libraries)

In a 2018 article, Christos Lynteris examines the invention of the "anti-plague mask" from an anthropological point of view, highlighting its impact on the identity. Recounting the history of the mask as the "march of medical reason" allows Lynteris to address—years before the COVID-19, in the context of recent diseases like SARS, MERS, and Ebola—the facemask's agency in transforming wearers into "reasoned" subjects lingering on the edge of the "next pandemic."

"If it could defend doctors and the general population from plague, this was possible only because it both stopped germs from entering the human body and transformed the public from a superstitious and ignorant mass into an enlightened hygienic-minded population: a population that accepted the contagious nature of the disease and corresponding, often brutal, quarantine and isolation measures."

The London School of Economics and Political Science / Gerard Delanty: Six Political Philosophies in Search of a Virus: Critical Perspectives on the Coronavirus Pandemic

(Photo: Commanding General, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, briefs media on COVID-19 response. / Marv Lynchard / DVIDS)

The sociologist Gerard Delanty explores the limits of older philosophical theories like utilitarianism, Kantianism, and libertarianism, and overviews recent predictions of future social orders, from epidemiological governance, to the reinvention of Communism and the struggle against the climate regime.

"[P]eople do not act rationally (Brexit is ample proof of this). What we need to understand is the nature of irrationality in order that it can be controlled. Now, such methods of control are not authoritarian as such (as in lockdown policies) but ‘nudges’ and can be done with the support of people who believe that they are making their own choices without the heavy hand of the state forcing them. Nudge theory is in fact quite close to Foucault’s later notion of discipline as governmentality, which requires liberty for its effectiveness."

(Photo: EJIL:Talk! / engin akyurt on Unsplash)

Acknowledging that COVID-19 is a threat against which states have the obligation to protect the right to life and health, Lorna McGregor, a Professor of International Human Rights Law, poses three questions states must be able to answer, in order to justify the introduction of contact-tracing apps as their response to the epidemic. Her article suggests, however, that even in spite of meeting the requirements of scientific legitimacy, data protection, and public oversight, an exceptional use of contact-tracing will inevitably further its risks to human rights.

"[S]tates therefore need to be proactive in fully recognising the impact these technologies have on human rights and make clear commitments to never use such technologies where alternatives exist. They also need to ensure a strong multilateral and multistakeholder accountability and review framework".

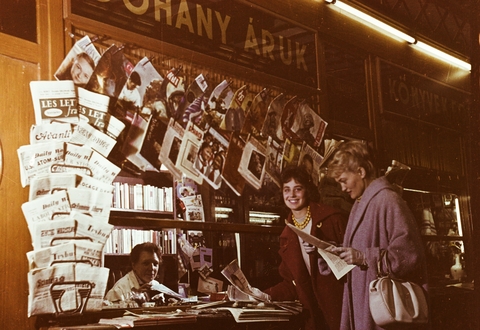

The Lawfare Podcast / Jack Goldsmith: David Kaye on Free Speech During a Pandemic

(Photo: Press monitoring in Hungary, 1966 / Fortepan)

Interview with David Kaye, UN Special Rapporteur, on his report on disease pandemics and the freedom of opinion and expression. After summarizing what actually the freedom of opinion involves, Kaye urges to remind governments not only of their responsibility not to interfere with expression, but also of their obligation to ensure access to information. He then stresses that governments can restrict expression to protect legitimate objectives—such as health—only if provided by law that is transparent and explicit.

"The problem with government putting this kind of pressure on the companies to take down content is a break in democratic accountability mechanisms. If government believes that the mere publication of these kinds of events is a threat to public health, they should use their tools to order Facebook to take that stuff down, and then face the democratic consequences of that. But if you just sort of suggest it, and Facebook behaves, what do we as citizens do, when we want to complain about that?"

QUB School of Law / All Island Conversation around Covid 19 and Human Rights – Seminar 1 – Emergency Powers

In a QUB School of Law webinar, UN Special Rapporteur for the Protection and Promotion of Human Rights Fionnuala Ní Aoláin outlines the concept and the requirements of governmental emergency powers, i.e. the right to limit rights, as accepted by the international human rights system. She also presents the new challenges her office faces, warning that undoing emergency powers tends to be extremely difficult.

"Instead of seeing a piece of legislation entitled 'emergency powers related to the COVID crisis,' we’re seeing things called Health Bills or Sanitation Bills, where it’s not obvious that they are in fact a piece of an exceptional legislation. So even finding what is exceptional in the terrain of powers being used by the state can often be difficult. That’s one very obvious trend we’ve seen generally since the events of 9/11, but I think it’s also pertinent to the COVID-crisis, that states are increasingly not proclaiming or naming that they’re in an exceptional situation."

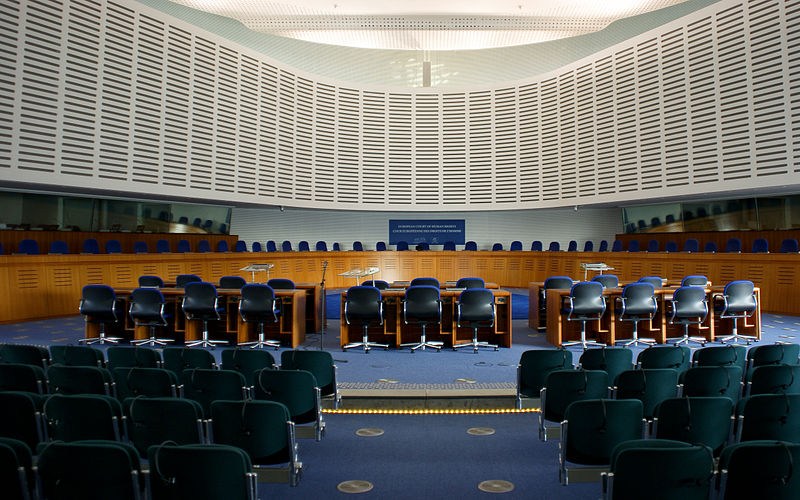

Verfassungsblog / Alice Donald and Philip Leach: Human Rights – The Essential Frame of Reference in the Global Response to COVID-19

(Photo: Grand Chamber of the European Court of Human Rights / Wikimedia)

Dr. Alice Donald and Philip Leach propose to realize human rights as the framework to tackle the structural inequalities revealed by the outbreak, arguing that governments that fail to ensure people’s rights, or abuse them, also fail in responding to the pandemic. Furthermore, the authors urge to explore how this framework needs to be developed, e.g. by understanding the access to the Internet and to health care as fundamental rights.

"Just as states are seeking to get ahead of the COVID-19 curve, so must human rights advocates steal a march on those who would use the emergency opportunistically to erode human rights, democracy and the rule of law. This means rethinking the role of the state from a human rights perspective, asking what the state is obliged to do for and with us and not just what it has the power to do to us."

Revolved around Katya Cengel’s book From Chernobyl with Love: Reporting from the Ruins of the Soviet Union, a discussion on the similar challenges and dangers journalism faces in reporting distant disasters like Chernobyl and the COVID-19 pandemic. While Katya Cengel focuses on reporting on the 1986 Chernobyl disaster, Jin Ding and Courtney Radisch present how authorities today obstruct access to information and create hostile environments for journalists, whether in China, the Middle East, or the USA.

"[W]e have seen now a shift in the use of fake news to delegitimize reporting and to restrict journalism and even criminalize journalism. Throughout the Middle East, we see that the use of fake news laws are being used to intimidate, threaten, and arrest journalists. We're also seeing this in parts of Africa, in Europe, for example in Hungary, in Latin America, so really this is now a global pandemic."

Yes! Magazine / Nataliya Braginsky: Chernobyl Is My Inheritance, but It Has Lessons for Us All

(Photos: Chernobyl, 1990; California, 2020. / Yes! Magazin / Wojtek Laski/Getty Images; Leonard Ortiz/MediaNews Group/Orange County Register/Getty Images)

Nataliya Braginsky, a Ukrainian immigrant, discovering similarities between Chernobyl and the current pandemic; from the invisibility of radioactivity and SARS-CoV-2, resulting in abstract and technical efforts to measure them, to toxic racism or discrimination on the one hand, and mutual aid and solidarity on the other. She cites Gorbachev naming in 2006 the Chernobyl disaster as the main cause of the USSR's collapse, hinting at the possible level of the outbreak's consequences on the USA and on capitalism.

"My parents recalled the scanning of all who disembarked the train in St. Petersburg seeking refuge. My sister’s shoes signaled an alert and were confiscated. The memory of her white sandals and the sound they produced have become a kind of archive, a recollection we can see and hear to convince us that it really happened."

Internet Archive / Chris Freeland: Forging a Cooperative Path Forward: University Presses & the National Emergency Library

(Image: Internet Archive)

Chris Freeland, Director of Open Libraries at the Internet Archives, on why they launched the National Emergency Library (NEL), a temporary collection of books for remote teaching and research. Although university presses initially objected to the use of their publications, a discussion exploring common goals resulted in a productive cooperation (and a reusable statement ).

"The materials published by university presses represent the preeminent scholarly output of America’s research universities. They present peer-reviewed research and analysis of use to policymakers and scholars, and provide materials that help shape and inform a literate and informed culture. In short, university press books are exactly the kind of content that people need access to right now."

Project Syndicate / William A. Haseltine: What AIDS Taught Us About Fighting Pandemics

(Photo: Mara Haseltine's 2006 sculpture SARS Inhibited in Singapore, representing the effect of an abandoned drug candidate on the SARS virus. / Project Syndicate)

A call by William A. Haseltine, an infectious disease expert and the Chair and President of the global health think tank ACCESS Health International, not to repeat the mistakes of the AIDS crisis. Being one of the few who, during the 1980s, studied the HIV disease despite the negligence he faced when seeking funds, he warns about the similar tendencies in responses to SARS viruses, and points to governments' responsibility in financing research.

"SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) was first reported in 2003 . . . . in the years since, policymakers and the public have been warned about the potential for future outbreaks, and about the need to learn from the past. We didn’t. While funding was made available to develop a medical solution for SARS and MERS at the height of those outbreaks, it dried up after the initial panic passed."

(Photo: Vegetables market during ongoing COVID-19 lockdown, in Jalandhar, Monday, April 20, 2020. The Wire / PTI)

Shohini Sengupta argues that the role and the language of legislation often correlate, therefore a linguistic approach to regulations may reveal underlying intentions. After summarizing a research done on the 2008 crisis management in retrospect, she urges to study the responses to the current crisis in real time.

"[T]he 'length,' i.e., on the amount of linguistic material a reader has to retrieve, integrate and keep in working memory for comprehension, the 'lexical diversity,' i.e., the proportion of new concepts that inhibited faster comprehension, and the use of 'conditional clauses' requiring integrating different exceptions or constructing hypothetical events."

openDemocracy / Hanna Meretoja: Stop Narrating the Pandemic as a Story of War

(Image: openDemocracy / Pixabay/TheDigitalArtist. Pixabay licence)

Hanna Meretoja presents how narrating the COVID-19 pandemic as a war justifies emergency legislation, conceals structural inequalities by interpreting sickness as a fight depending upon patients' strenght, and rationalizes the sacrifices of and casualties among "essential workers" turned now into war heroes.

"Not only is the analogy of war misplaced on factual grounds; it also misses the possibility to cultivate an imagination that builds on narratives of peace, solidarity and social justice—and to foster a more acute understanding of how we are all fundamentally dependent on one another as inhabitants of a shared planet. This is an opportunity to embrace our shared vulnerability and destructibility."

VOX, CEPR Policy Portal / Nicolas Ajzenman, Tiago Cavalcanti, and Daniel Da Mata: Leaders' Speech and Risky Behaviour During a Pandemic

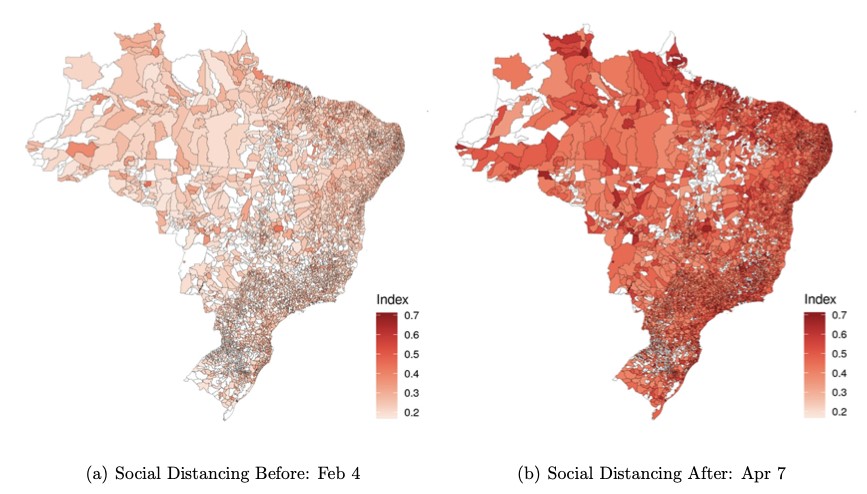

(Image: Social distance index in Brazil on 4 February and 7 April. / voxeu.org)

A paper investigating how Brazilian president Bolsonaro's speeches affected compliance with social-distancing policies. Comparing changes in GPS-based civilian mobility values before and after Bolsonaro's addresses, and combining this with electoral data indicating political preferences, the authors find that social distancing dropped in pro-Bolsonaro municipalities.

"A political leader’s recommendations on preventive behaviour are taken seriously by followers, regardless of how scientifically sound the statements are. For instance, after President Trump suggested that disinfectant could be injected as a remedy against coronavirus, there was a rise in interest in (and eventually purchase of) disinfectant."

Digital Preservation Coalition / Sara Day Thomson: If These WARCs Could Talk: Learning from Archived Web & Social Media Covid-19 Collections

(Image: Digital Preservation Coalition)

The DPC’s Web Archiving & Preservation Working Group on recording online responses to the coronavirus outbreak, from governments and health authorities, thus tracking the course of decision-making, to news sites and social media, potentially revealing how information spread. To support this work, the DPC produced guides for archiving web and social media content.

"For those of us living this pandemic in real time, the situation is raw, uncertain, rife with fear, anger, and confusion. Web and social media archives have the potential to one day provide the basis for clarity and understanding, for holding governments to account for their preparedness and decision-making. However, these archives are only as valuable as they are accessible and only as effective as they are used."

Q&A with dr. Howard Markel, director at the University of Michigan's Center for the History of Medicine, currently collaborating with the CDC to study the efficacy of lockdown measures during the 1918–1919 flu pandemic in the US. He stresses, however, that comparisons must be drawn carefully, since 1918 was very different and the knowledge on infectious diseases was limited.

"If you look at what happened right after 1918–1919, was the Roaring Twenties. The stock market went up to incredible heights before plummeting in 1929. As F. Scott Fitzgerald called it, it was the gaudiest, grandest spree in American history. People socialized, popular music and popular entertainment bourgeoned, the movies developed, radio developed—there were a lot of wonderful things that begin the 20th century as we know it in the 1920s. From my perspective, history does not show that society changes entirely after an epidemic or a pandemic. In fact, we have lots of evidence to show to the contrary."

Federal Reserve Bank of New York / Kristian S. Blickle: Pandemics Change Cities: Municipal Spending and Voter Extremism in Germany, 1918-1933

(Photo: Georg Pahl: Campaigning in front of a polling place in Berlin, 1932. German Federal Archives / Wikimedia)

A report evaluating and combining data from interwar Germany on the 1918 flu pandemic, city spendings, and election results. The paper's main finding is that the 1918 influenza was a significant factor—besides the First World War, the Great Depression, austerity, and unemployement—driving voters toward the NSDAP. While cities with more flu victims spent less per capita on individuals, both mortality rates and declining city expenditures correlated with an increase in votes won by right-wing extremists.

”We argue that our results are likely the consequence of changes in societal preferences following a pandemic. In particular, the fact that the pandemic affected predominantly one part of the demographic spectrum, in this case younger people, may have altered preferences in communities. It may also have spurred resentment of foreigners among the survivors (as has happened in past pandemics)”.

(Image: Boston Review)

Recapping how hydroxychloroquine, an antimalarial drug Chinese researchers investigated as potential treatment for SARS-CoV-2, became Donald Trump's "miracle drug," Cailin O'Connor and James Owen Weatherall present the risks of pushing an essentially scientific matter into the political discourse prematurely. They argue that belief factions interpret news based on distinct political identities, which gives the phenomenon of misinformation a new framework not exclusively defined by the question of truth.

"[W]ith readers clamoring for the latest virus news, journalists are on the hunt for new articles they can report on, sometimes pushing claims into prime time before they’ve been properly vetted. All this means that there is a huge amount of information circulating that has some scientific legitimacy but that may be dramatically underdeveloped and more likely than normal scientific findings to be overturned."

(Photo: Preparation of measles vaccine at the Tirana (Albania) Institute of Hygiene and Epidemiology. Wikimedia / WHO)

Presuming that crises have a distorting effect on the pace and direction of scientific research, Kevin A. Bryan, Jorge Lemus, and Guillermo Marshall analyze how the COVID-19 pandemic impacted pharmaceutical firms. Their data suggest that the social pressure and/or the market opportunity to find quick solutions has resulted in fractured research processes and simpler, less valuable products; in order to prevent this, the authors propose several changes to governmental innovation policy.

"Our data shows that the rate of Covid-19 research, both pharmaceutical projects and related academic research, is an order of magnitude higher than any previous epidemic. As the Covid-19 pandemic became global in March 2020, the rate of pharmaceutical research rose even higher. This incredible pace of R&D is not all good news, however. Compared to previous epidemics, Covid-19 research pipelines are skewed towards repurposed drugs and non-vaccines.”

Science / Alex John London and Jonathan Kimmelman: Against Pandemic Research Exceptionalism

(Photo: Science / TED S. WARREN/AP PHOTO)

Alex John London and Jonathan Kimmelman oppose the common assumptions that in times of crisis may serve as justifications for "research exceptionalism," i.e. the temporal interruption of the high standards of quality in science. The authors see the social and scientific value of research in its ability to provide credible information reinforcing decision-making, and describe five fundamental preconditions research standards must meet.

"Even under normal conditions, the goal of research ethics and policy is to use regulations, reporting guidelines, and other social controls to align research conduct with the public interest. Crucially, the information that research produces is a public good on which caregivers, health systems, and policy-makers rely to efficiently discharge important moral responsibilities."

Fast Company / Samuel Cohn: A Brief History of People Refusing to Wear Masks

(Photo: Tram operator in Seattle refusing man without mask during the 1918 pandemic. Wikimedia)

Samuel Cohn, a professor of history at the University of Glasgow, presents how societies responded to preventive measures during the 1918 flu pandemic, and especially to regulations that made face masks compulsory. Despite accepting more intrusive restrictions (like, in the US, the closure of cinemas or the fines against kissing outdoors), it were masks that people eventually objected to. Cohn suggests that this was partly because authorities and experts failed to clearly communicate their health benefits.

"There was scientific debate from the beginning about whether the masks were effective, but the game began to change after French bacteriologist Charles Nicolle discovered in October 1918 that the influenza was much smaller than any other known bacterium. The news spread rapidly, even in small-town American newspapers. Cartoons were published that read, 'like using barbed wire fences to shut out flies.' Yet this was just at the point that mortality rates were ramping up in the western states of the United States and Canada."

LSE IQ Podcast / Sue Windebank: What Does Gender Have to Do with Pandemics?

Interview with dr. Clare Wenham, Assistant Professor of Global Health Policy at LSE. Dr. Wenham explains the health and social-economic impacts of epidemics on women, from access to sexual reproductive health services to domestic violence and to unpaid household work. However, she also discusses why the coronavirus outbreak gives her hope with regards to the role of social sciences, and to greater gender-equality in the workplace.

"We know, for example, from the Ebola outbreak that when health systems become overwhelmed by a crisis, all the resources and all the activity gets diverted to respond to that crisis, which means that anything that is deemed nonessential gets left by the wayside. . . . [in West Africa] the same amount of women died of maternal complications, from not being able to seek maternal care, than died of Ebola in the same time period."

The MIT Press Reader / Lucas Richert: Of War, Collective Trauma, and the Coronavirus Crisis

(Photo: Antiwar demonstration at Fort Dix, N.J., 1969. The MIT Press Reader / Courtesy of Special Collections and Archives, Albertson and Simon Collections University of Massachusetts Amherst)

Lucas Richert recounts how the Vietnam War’s impact on mental health and on psychiatry eventually contributed to the official recognition of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). However, what he finds seems to be a professional conflict parallel to the actual war, with experts, then rendered radicals, obstructed in fulfilling their duties to "recognize and communicate hard reality, however painful that truth" was.

"[C]urrent discussions about coronavirus trauma clearly echo those that followed the Vietnam War: the need for clear-eyed recognition of a health problem and an evidence-based approach; the suitable concentration of medical and financial resources at both the federal and state levels; and concerns about returning home after being abroad."

(Image: Project Syndicate / erhui1979/Getty Images)

Maciej Kisilowski (CEU) and Anna Wojciuk (University of Warsaw) claim that COVID-19 exposed populism's inability to handle complex issues, and urge democratic parties to form national unity governments, carefully considering the inclusion of populists.

"National unity governments involve an exceptional degree of power sharing, which in turn confers the legitimacy needed to carry out increasingly difficult and costly decisions in the face of a crisis. They also can tap into a broader array of experts and experienced politicians to reach better decisions, and their cross-partisan structure ensures at least some oversight over executive power".

(Image: Logarithmic chart of COVID-19 Deaths per capita — Selected countries / Cepaluni, Dorsch, Branyiczki)

CEU researchers provide a quantitative examination on the connection between political systems and COVID-19 deaths, to investigate the impact governmental forms had on the efficiency and speed of policy responses. As available data imply that more liberal countries recorded more per capita deaths and sooner, the authors urge democracies to acknowledge and address the disadvantages of their political institutions in order to prevent the loss of trust in democratic governance.

"The coercive power of some non-democratic countries may have provided them with an early advantage in reducing deaths in this pandemic. However, the freedom of information and research available in democratic countries might help them over time to reverse the autocratic advantage we document in this paper. Therefore, we hope that our paper reignites the broader debate about the trade-off that democratic societies must grapple with".

(Video: Shelter in Place with Shane Smith & Edward Snowden / Vice)

Interview with Edward Snowden on what he calls "the architecture of oppression," the construction of which is not founded on science but on political intentions. He reminds, however, that the same moment political powers currently utilize to extend social control, grants us the opportunity for revolutionary changes.

"[W]hen any of us look at where this is heading, we need to think about where we’ve been. And sadly, these kind of emergency powers that are born out of crises, have a perfect history of abuse. Whenever you look at these things, the funniest part about it in a dark way, is that the emergency never ends. It becomes normalized."

The Guardian / Jana Bacevic: There's No Such Thing as Just “Following the Science” – Coronavirus Advice Is Political

(Photo: The Guardian / Paul Ellis/AFP via Getty Images)

As governments across the world claim to make pandemic policies by "following the science," Jana Bacevic, a Cambridge University sociologist, reveals the non-scientific actors of scientific research. She sheds light on how the complex relationship between science, politics, and society, is affected, besides scientific knowledge, also by economic calculations, moral and ideological commitment, and even opinion polling.

"Scientists can tell politicians the conditions under which their models are likely to work, but they are not responsible for creating those conditions. Blaming epidemiologists for the consequences of the government’s Covid-19 strategy is like blaming climate scientists for not preventing the climate crisis. Scientists can provide evidence, but acting on that evidence requires political will."

The National Archives / Free Access to Digital Records

(Photo: TNA blog)

The National Archives has made its entire digital repository—over 5% of all records—available online, until reading rooms are closed. TNA, the official archive of the UK government, England, and Wales, was created with the merger of four separate institutions founded between 1786 and 2005: the Public Record Office, the Royal Commission on Historical Manuscripts, Her Majesty's Stationery Office, and the Office of Public Sector Information. The more than 80 million documents now available online include:

"First and Second World War records, including medal index cards; Military records, including unit war diaries; Royal and Merchant Navy records, including Royal Marine service records; Wills from the jurisdiction of the Prerogative Court of Canterbury; Migration records, including aliens’ registration cards and naturalisation case papers; 20th century Cabinet Papers and Security Service files"

Foreign Affairs / Barry R. Posen: Do Pandemics Promote Peace?

(Photo: Serbian soldiers stand guard at Serbia's Batrovci border crossing with Croatia, March, 2020. Foreign Affairs / Marko Djurica / Reuters)

Addressing the question in its title, the article by Barry R. Posen, a political scientists and Director Emeritus of the MIT Security Studies Program, argues that starting wars needs the optimistic belief in victory, while the discouraging effect of pessimism mostly maintains peace. Responding to fears of a coming war, Posen describes economic as well as strategic reasons why a pandemic is not the time for armed conflicts. Looking beyond COVID-19, he predicts changing trends in trade and in the trust toward governments, with the focus on domestic recovery.

"Scholars have documented again and again how war creates permissive conditions for disease—in armies as well as civilians in the fought-over territories. But one seldom finds any discussion of epidemics causing wars or of wars deliberately started in the middle of widespread outbreaks of infectious disease."

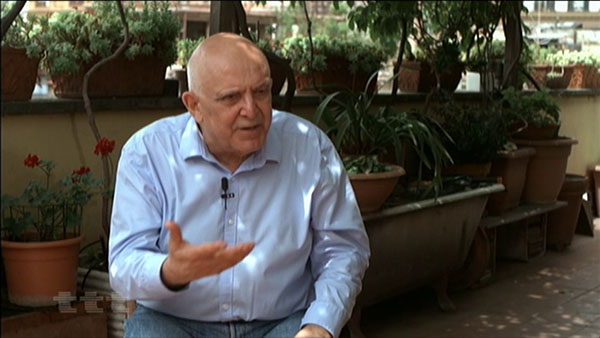

New Left Review / Marco D'Eramo: The Philosopher’s Epidemic

(Photo: franzjosefadrian.com / ARD)

Commentary by Marco D’Eramo to the various understandings of the pandemic and to the predictions of post-pandemic futures. From Foucault’s leprosy and plague models to 9/11 and to 2008, D’Eramo reveals how the current crisis differs from the historical scenarios either philosophers, investors, or politicians refer to.

"During wartime, both financial and material capital is demolished: infrastructures, factories, bridges, ports, stations, airports, buildings. But once the war is over a period of reconstruction begins . . . . However, the current epidemic looks more like a neutrino bomb, which kills humans and leaves buildings, roads and factories intact (if empty). So, when the epidemic is over, there will be nothing to rebuild—and no consequent recovery."

LSE Business Review / Michael Muthukrishna: Cultural Evolution, Covid-19, and Preparing for What’s Next

(Image: LSE / GDJ)

Arguing that the professionals at the forefront of the pandemic, whether epidemiologists, economists, or data scientists, do not work in an isolated, neutral discourse, Muthukrishna, a professor of economic psychology, presents why understanding the beliefs, behaviours, and normative institutions shaping our response to the current crisis, is necessary to prepare for future ones.

“Only by creating conditions in which diverse cultural-groups can attempt different strategies that search through the space of solutions, but also creating conditions in which accurate data, strategies, failures and solutions are shared, can we hope to maximise the potential of our collective brains.”

(Photo: The skeleton of Byrne displayed at the Royal College of Surgeons. / StoneColdCrazy at English Wikipedia)

Angela Stienne raises the question of the ethical representation of illnesses, which museum professionals will have to address, before narrating the COVID-19 crisis. Dr. Stienne warns that while invisible illnesses may be difficult to exhibit, the incorrect demonstration of diseases and disabilites, and especially their subjects, easily leads to derogatory approaches and discrimination.

"[U]ntil its recent temporary closure, the Hunterian Museum in London displayed the skeleton of Charles Byrne, an Irishman born in the 18th century who had a genetic condition called gigantism. Prior to his death, he expressed the desire to be buried in the sea, but instead, his body was snatched and then acquired by surgeon John Hunter. On the latter’s death, Byrne’s body became part of the Hunterian Museum of Anatomy. In numerous museums, human remains are allegedly displayed for educational purposes, without considering the message this sends to disabled visitors or those suffering from invisible illnesses."

Global News / Eloise Therien: Galt Museum & Archives Bringing Exhibits Online, Creating Interactive Videos for Lethbridgians

(Photo: The Galt Museum's 2018 exhibition Pandemic at Home: The 1918–1919 Flu, now online at galtmuseum.com)

A fresh example of how archives and museums can cope with the forced closing of their research rooms and exhibition spaces. The Galt Museum and Archives in Lethbridge, the regional museum for southern Alberta, provides historical information on the human history of the area from Blackfoot culture, to coal mining, to regional breweries. Usually hosting over 50,000 visitors yearly, the museum has moved its activities online in an effort to continue to present their collections and expertise to its audiences.

"Some of the newest additions to the online platform include: Building Bridges: an interactive YouTube video on bridge building and history; War on Grasshoppers: Just Gas Them!: a short article on insect extermination attempts; Tips and Tricks for Archiving: Labelling Memories: a practical 'how-to' guide for record-keeping at home."

American Alliance of Museums / Marjorie Schwarzer: Lessons from History: Museums and Pandemics

(Photo: An art gallery in California turned into an 80-bed emergency hospital during the 1918 flu. Oakland Public Library)

The Center for the Future Of Museums Blog of the American Alliance of Museums revisits the responses of US museums to past health crises, to demonstrate institutional potentials to museums today. During the tubercolosis crisis, educational exhibitions promoted prevention and self-care; museums during the 1918 flu epidemic substituted closed schools, and in some cases, hospitals; and to combat the AIDS crisis, the Centers for Disease Control collaborated with museums to present the personal stories of people living with HIV.

"With so many mixed messages coming from the federal government and media, the COVID-19 pandemic calls on those of us working in museums to provide a fact-based, scientific, and humanistic appraisal of the situation. Obviously, museums cannot be on the frontlines of health care and epidemiology. But we can provide critical perspective on broader developments and trends. And we can think about what the public will want to know about this moment in the future."

The New York Review of Books / Shannon Pufahl: Numbering the Dead

(Photo: Cemetery workers in Brazil, April 18, 2020. The New York Review of Books / Fabio Teixeira/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images)

Shannon Pufahl recounts the history of numbering people; from why Americans began counting the dead during the Civil War, to masses during the French Revolution turned into representative groups and into majorities or minorities, to their differentiation during the 20th century according to class, gender, race, etc. Claiming that statistics has always served a purpose, whether managing grief or societies, she urges to reassess our understandings of mass and individual.

"[N]ow the tabulation of human existence within geopolitical borders has another, mortally important aim. Surely the distribution of a Covid-19 vaccine—when or if one is developed—will be determined in part by how many people live where, how many people are known to have been ill or died."

(Photo: Wikipedia / Lynn Gilbert)

Originally published in the New York Review of Books in 1978, Susan Sontag’s Illness as Metaphor attempts to overview the different fantasies mankind attributed to tuberculosis and cancer in order to prevent having to directly address them. According to Sontag, these metaphors, as well as the general adjectives illnesses become, not only reveal the changing perceptions of specific diseases, but allow a complex understanding of the social, political, mental conditions of past periods. Her conclusive sentences suggest that becoming aware of the language used to describe illnesses today may be beneficial for shaping the future.

"Since the interest of the metaphor is precisely that it refers to a disease so overlaid with mystification, so charged with the fantasy of inescapable fatality. Since our views about cancer, and the metaphors we have imposed on it, are so much a vehicle for the large insufficiencies of this culture, for our shallow attitude toward death, for our anxieties about feeling, for our reckless improvident responses to our real 'problems of growth,' for our inability to construct an advanced industrial society which properly regulates consumption, and for our justified fears of the increasingly violent course of history."

Verso Blog / Nathalie Olah: Viral Terminology, Technology and Capitalism

(Photo / Verso Blog)

Nathalie Olah, author of the book Steal as Much as You Can, argues that the battle of how we narrate the current pandemic is going to have a crucial impact on whether we will be able to internalize the lessons of the crisis. As an alarming case in history, she present how the AIDS crisis was mismanaged in this regard.

"The metaphorical connections between technological systems, sexual intercourse and the transmission of disease would continue apace throughout the decade, forming part of a 'safe computing' culture as alarmist and censorious as the earlier safe sex campaigns. . . . the technology industry and its partners in government were able to further stigmatize queer culture perceived as being divergent and therefore 'harmful' and 'destructive' to the neoliberal hegemony and a work culture that was steadily expanding, and encroaching on the home."

The New England Journal of Medicine / Allan M. Brandt, Ph.D., and Alyssa Botelho, A.B.: Not a Perfect Storm — Covid-19 and the Importance of Language

(Photo: Wikipedia / Arnold Paul)

Brandt and Botelho, two scholars of the history of medicine, point to the frequent use of the phrase "a perfect storm" in connection with the current pandemic, as well as with previous zoonotic diseases like SARS, H1N1 influenza, and Ebola, and even the opioid crisis. The authors sharply oppose describing these events with an expression that falsely suggests unpredictability and inevitability.

"[E]ven so-called natural disasters are not perfect storms. Crises such as Hurricane Katrina in 2005 and the 2010 earthquake in Haiti had such extreme effects on morbidity and mortality because of long-standing histories of political disenfranchisement and neglect of infrastructure in the affected regions. In the setting of anthropogenic climate change, perfect-storm language eludes important conversations about our responsibility for the frequency of both emerging zoonoses and extreme weather events—as well as the disproportionate effects of these crises on the world’s most vulnerable people."

(Photo: A seasonal harvest worker from Romania instructed at the Berlin-Schoenefeld airport. Balkan Insight / EPA-EFE/CLEMENS BILAN)

Through Romanian workers' conditions in Germany, Raluca Bejan addresses the ways the pandemic impacts migrant workers. She argues that the exceptions made to sustain the flow of cheap labour from poorer countries amid lockdowns, border closures, health regulations, and social distancing, have exposed the unequal relations between EU countries.

"Seasonal workers are now staying longer in order to limit any additional movement that would contaminate domestic bodies, but without receiving any additional welfare benefits for this extended stay. The pandemic has now made it easier to extract more labour from seasonal workers without the obligation of increased welfare provisions."

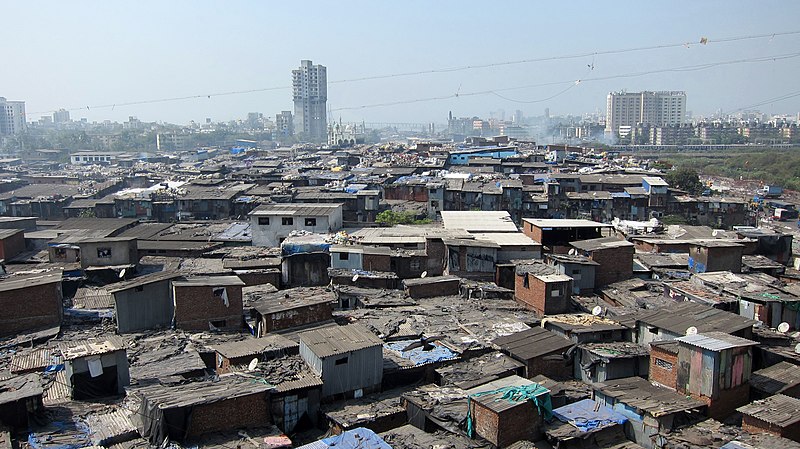

Bloomberg / Dhwani Pandya and Ari Altstedter: Trump-Backed Drug to Be Tested on Thousands in Mumbai Slums

(Photo: Dharavi, one of the test locations / Wikipedia)

A Bloomberg report on a planned drug test in Mumbai, India’s major virus hotspot. Despite known side effects and little evidence on its effectiveness against SARS-CoV-2, the experiment with hydroxychloroquine, an anti-malarial medication, will be conducted in two densely-packed slums.

"The move underscores the desperation and mounting pressure on health care officials for solutions against a novel pathogen which has infected over 2.1 million people globally and killed over 146,000. It also explains the frenzied excitement over a decades-old drug—U.S. President Donald Trump called it a 'game changer' in the fight against the virus—despite a patchy efficacy record in some small studies and a documented list of side effects."

Eurozine / Koray Caliskan, Donald MacKenzie: Of Viruses and Men

(Photo: Eurozine / ål nik on Unsplash)

An attempt to explain current conditions from the angle of social sciences, a field that has failed to identify pathogens as actors in social processes. To have the necessary tools to study "the first truly global social experiment," liberating the social sciences from their anthropocentric framework has become fundamental.

"After this pandemic is over, we need to rewrite every social science book. We need to stop ignoring how humans and non-humans interact. Among all of the things that humans are, we are the hosts of viruses. The Earth is not a passive stage on which we act out the theatre of human interaction but is—in the fullest sense—our host. We need to incorporate planetary considerations into our economic calculations."

In The Moment (Critical Inquiry) / Bruno Latour: Is This a Dress Rehearsal?

(Image: Pieter Bruegel the Elder: The Fight Between Carnival and Lent / Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien, Bilddatenbank)

Bruno Latour, the renowned philosopher, anthropologist, and sociologist investigates the assumption whether the "obligatory fast" that the pandemic is may prepare humanity to face the climate crisis. The outbreak forced states to act, or it created an opportunity for leaders to safeguard their citizens at least; and it is a similar realization the fight against climate change needs. Yet, Latour claims that the current world order organized around pedantic nation states is not fit for that fight.

"[I]n the health crisis, it may be true that humans as a whole are 'fighting' against viruses—even if they have no interest in us and go their way from throat to throat killing us without meaning to. The situation is tragically reversed in ecological change: this time, the pathogen whose terrible virulence has changed the living conditions of all the inhabitants of the planet is not the virus at all, it is humanity!"

Boston Review / Yasheng Huang: No, Autocracies Aren't Better for Public Health

(Photo: Boston Review / Flickr / Gauthier DELECROIX)

After providing a historical context to China's handling of the epidemic, Yasheng Huang addresses the question whether, in general, autocracies or democracies are more capable of preventing outbreaks. His main argument is that although the excessive power autocracies hold may be benefitial (and justified by) in their response to this health crisis, the crisis itself could have been prevented, had the Chinese state not silenced the first warnings about SARS-CoV-2. Repressing information, however, is a basic autocratic reflex.

"If people insist on attributing China’s curve flattening to the superiority of the Chinese system, they should at least be more precise in their flattery. A more accurate statement would go something like this: the Chinese system is successful in creating a problem that it is also successful at solving."

(Photo: Jacobin / Cindy Ord / Getty)

Nicole Aschoff recaps the developing sings of digital surveillance since the coronavirus. Acknowledging the general support for tech-based preventive solutions, she overviews the fears raised by experts regarding the intrusive nature of tracking apps—whether installed voluntarily or by order—and the expanding cooperation between authorities and tech companies. She notes, however, that the outbreak did not produce these tensions between privacy and technology, it only made them more visible.

"In this crisis governments and companies are relying on these habits and expectations, adapting our existing relationships with our smartphones to serve the end of quelling the viral outbreak. Indeed, the ease with which these habits and expectations have become repurposed is evidence of how ingrained they’ve become as smartphones have become ubiquitous over the past decade."

openDemocracy / Martina Tazzioli: COVID’s Borders: Between Peer-to-Peer Surveillance and the “Common Good"

(Photo: Trieste, March 14, 2020 / openDemocracy / Jacopo Landi/PA. All rights reserved)

Martina Tazzioli, a lecturer at Goldsmiths, attempts the parallel analysis of two essential aspects of the pandemic, the question of public responsibility and that of common good. Looking at examples from Italy, she finds that the phenomenon of citizens practicing control over each other suggests a consensus that surveillance, whether top-down or peer-to-peer, served the common good. From this point of view, Tazzioli warns, there is a thin line between collective responsibility and mutual suspicion, while the "common" in common good is often based on exclusion.

"[T]he ideas of 'common good' and 'public responsibility' which underpin the wide acceptance of peer-to-peer surveillance measures are structured around a series of exclusionary boundaries, some of which are quite sharp—citizens vs migrants—while some others are more invisible but no less violent – such as workers exposed to the virus."

The New York Times / Kathryn Olivarius: The Dangerous History of Immunoprivilege

(Image: Two poor men dying in Jackson Square, New Orleans. / The New York Times / Bettman Archive, via Getty Images)

From "immunity passports" to "immunocapital" and to "immunoprivilege," Kathryn Olivarius presents the consequences of "immunological discrimination" in 19th-century New Orleans. Then, yellow fever epidemics were used to further deepen the pre-existing social inequalities and the exploitation of the poor, temporarily replacing social status with "immunity status," without, however, actually changing the social pyramid. Today, Olivarius warns, we face the similar case of "corona-capitalism," the impact and experience of which immensely differs between particular social groups.

"From the start, wealthy white New Orleanians made sure that while mosquitoes were equal-opportunity vectors, yellow fever would be anything but colorblind. Pro-slavery theorists used yellow fever to argue that racial slavery was natural, even humanitarian, because it allowed whites to socially distance themselves; they could stay at home, in relative safety, if black people were forced to labor and trade on their behalf."

The New Yorker / Masha Gessen: What Lessons Does the AIDS Crisis Offer for the Coronavirus Pandemic?

(Photo: AIDS memorial quilts in San Francisco, in 1995. The New Yorker / by Paul Fusco / Magnum)

Masha Gessen, after recounting the pros and cons from the ongoing debate whether comparing the current pandemic to the AIDS epidemic is possible, claims one of the many lessons of the latter to be scarily relevant. She argues that while blaming and discriminating mechanisms are already at play today, the individual struggles of living through the AIDS crisis are hardly remembered. In order to prevent the same from happening again, she urges us to "think of the pandemic as our problem."

"[I]t will end. And, unless we start the work of noticing and remembering now, we will forget how low we went. We will assimilate the ways in which the virus has changed our perceptions. We will romanticize the heroism and ingenuity of people who were betrayed by their government, rather than confront the people responsible for the betrayal."

(Photo: Closed playground in Bonn, April 6, 2020. / EHortenbach, coronarchiv)

An interview with Professor Thorsten Logge from the University of Hamburg, who is one of the founders of the coronarchiv, an open-access, crowd-sourced platform collecting memorabilia related to our coronavirus experience. According to its initators, the coronarchive is a flexible tool providing future historians with diverse material on the historic moment of the pandemic, documenting, hopefully, the individual, personal side of the period. The collection—comprising digital as well as physical items—will be handed over to local history and medical museums.

"[E]ach and every object is unique in its genesis and in its meaning for the person who contributed it. What I find most unusual and surprising is the broadness and the individuality of the material that comes to us in such diverse media formats. Maybe my favorite object is the coronarchiv itself, as a trace and source for our specific understanding of history, public history and historiography in the early 2020s."

Social Publishers Foundation / Lonnie Rowell: Knowledge Democracy at Work: Glimpses of Social Solidarity in the Pandemic

(Photo: Jan – Webster Groves, Missouri, USA / ARNA Social Solidarity Project Gallery)

The Social Solidarity Project is a participatory action research initiative. The project aims to emphasize the significance of communities, especially in a time of social distancing and constant fear, by launching an open-access, crowd-sourced photo gallery gathering images that capture the notion of solidarity in some way. Anyone can contribute to the project by sendind their photos with short descriptions (the call is available in several languages).

"We also hope to contribute to national and global public health considerations of the increased risks faced by populations already at-risk of marginalization in the sweeping narratives of geo-political upheavals. While celebrities, the wealthy, and the privileged in general have greater resources for staying sheltered, fed, cared for and in contact with loved ones, others, such as refugees, the homeless, migratory immigrants, and those confined to institutionalized settings associated with criminal and juvenile justice, mental health, and elder care are not so fortunate."

(Photo: Tent city near the Kremlin in 1990. The New York Times / Peter Turnley/Corbis -- VCG, via Getty Images)

Chris Miller, an economic historian, proposes an uncommon comparison to the consequences of the current pandemic; the collapse of the Soviet Union. The split of the "'globalized' socialist economy" had symptoms familiar today: production dropped, newly erected borders obstructed labor flow and transport, a shortage in supplies, and a fall in living expectancy.

"[B]y 1990, the party caught an infection, a crisis of legitimacy that reached epidemic proportions. Its influence waned, powerful regional leaders questioned its authority, and its control over the Soviet economy disappeared almost overnight. Soon anti-Communist leaders took power. This had the effect of a hurricane slamming into the Soviet economy—and then hovering over the country for a decade. In the absence of Communist Party diktats, industry had no instructions to follow."

Reuters / Michael Kahn, Joanna Plucinska: Closed Borders, No Shops? Been There, Done That, Say East Europeans

(Photo: Reuters / David W Cerny)

A Reuters report echoing from the former Eastern Bloc a feeling of nostalgia (and also, perhaps, a feeling of preparedness) regarding the sudden shortage in basic goods, the queues in front of grocery stores, or the restrictions on movement. However, people in the postsocialist countries of Eastern Europe are also reminded today of the consequences of the excess power authoritarian regimes held before the 1989–1990 changes.

"Access to trustworthy news sources today has also eased the strain for those who remember Moscow-dominated rule that ended in a series of mostly peaceful revolutions in 1989. Under Communism, governments that nobody trusted were the main source of people’s information in a pre-Internet world."

(Photo: The Washington Post / Tony Karumba/AFP via Getty Images)

Patrick Gathara presents the Kenyan government's response to the COVID-19 outbreak, which, he points out, very much recalls colonial times, with seemingly more effort put into sustaining obedience than into preparing and protecting the population againts the virus. Backed by a loyal media, the state rather announces directives instead of explaining decisions, let alone debating them, which often results in a lack of vital information, contradicting statements, and even the harassment of critical voices.

"[F]or the nearly two-thirds of the population in the capital Nairobi that is squeezed into cramped settlements that occupy just 6 percent of the city’s land, or the 8 in 10 workers providing manual labor in the informal sector, proposals such as social isolation and staying at home are completely impractical under the status quo."

Der Spiegel / Anne Backhaus: Battling Virulent Coronavirus Rumors in Africa

(Image: A fake UNICEF notice circulated in Ghana. / Der Spiegel)

As part of Der Spiegel's Global Societies project, Anne Backhaus reports on the many challenges the coronavirus outbreak poses to African countries, where, it seems, the pandemic is coupled with an "infodemic," a term coined by the WHO to describe the rapid and dangerous spread of misleading or inaccurate information, resulting not only in a lack of precaution, but also in unhealthy practices and discrimination. International organizations and local journalists combat fake news by establishing information centers, text message services, and even chatbots.

"In Ghana, several bars and restaurants have posted the fake UNICEF information on their websites to reassure guests. Once the incorrect advisories are disseminated by trustworthy people or organizations and considered valid, they quickly begin spreading by word of mouth. There are many people in the country who are unable to read, and people tend to trust family, friends and neighbors much more than they do government agencies."

GEN / Steve LeVine: How the Black Death Radically Changed the Course of History

(Image: GEN / Nick Sheeran)

Steve LeVine finds the 14th-century plague a better comparison to the current pandemic than either the 1918 flu or SARS; and not because of its immense deadliness. Based on the scale of the social changes that followed the plague, LeVine explores possible post-coronavirus futures, from the US becoming more self-reserved and China a "softpower superpower," to total corporate and governmental surveillance, and to a new labor movement.

"The wages of ordinary farmers and craftsmen had doubled and tripled, and nobles were knocked down a notch in social status. The church’s hold on society was damaged, and Western Europe’s feudal system was on its way out—an inflection point that opened the way to the Reformation and the even greater worker gains of the Industrial Revolution and beyond."

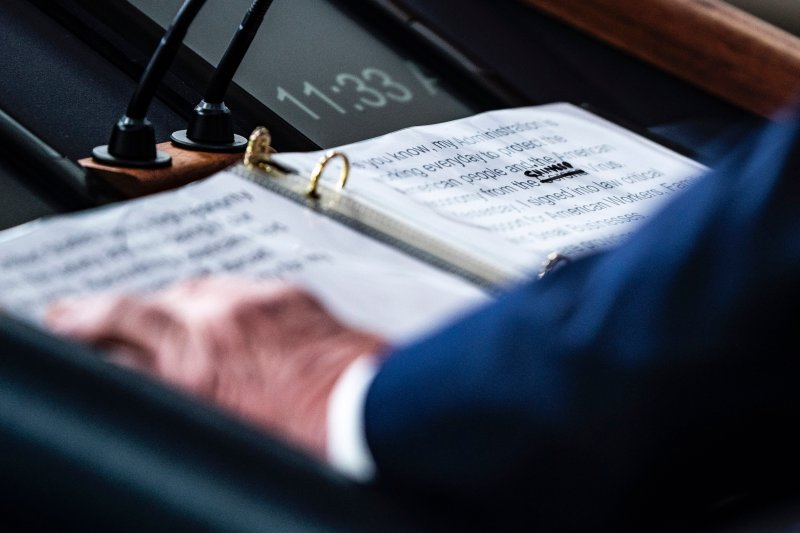

(Photo: "Corona" in President Trump's notes replaced with "Chinese" Virus. Time / Jabin Botsford—The Washington Post/Getty Images)

For weeks, President Trump had been tenacious in using "Chinese Virus" instead of coronavirus; similarly, the Hungarian government has repeatedly emphasized the foreign nature of the virus. The article in Time puts these instances of blaming foreigners for outbreaks into a historical narrative of mostly misleading names like "Spanish flu" or "Asiatic cholera," also presenting how these discriminatory phrases may be connected to laws differentiating "legal" and "illegal" immigration.

"A 1957–58 flu pandemic that was first identified in China became known as the 'Asian flu,' and a 1968–1969 flu pandemic first identified in Hong Kong became known as the 'Hong Kong flu.' Yet the 2009–2010 H1N1 flu that the CDC says was first recorded in the U.S. didn’t become the 'American flu.' Instead, it gained the misleading name 'swine flu' because scientists at first thought it was similar to viruses that occur in North American pigs".

(Photo: Michele Lancione / assemblinglight.com)

According to Lancione and Simone, the outbreak has introduced a new form of austerity, bioterity, justified by medical science and, basically, individual survival. First, they explore the theoretical roots and the first products of bioterity, then they argue that rediscovering solidarity may be the right response.

"[L]’emergenza is about using ‘health’ as a gateway to non-biological domains that are accessed rapidly and efficaciously precisely because of the biological foundation of emergency. This is a form of biologically-structured austerity—or what we provisionally call bioterity—that can strengthen old processes of governmentality. In other words, the affective capacities of current measures *might* foster subjectivities that not only desire their own repression, but willingly look for it in the name of perceived safety."

The Institute of Art and Ideas / Massimo Pigliucci: The Perils of Knowledge in a Pandemic

(Video: Massimo Pigliucci - Skepticism and Epistemic Virtue / Northeast Conference on Science and Skepticism)

After demonstrating a vast ammount of false information on coronavirus shared on social media or by news sites, Massimo Pigliucci argues that fighting misinformation is a collective ethical responsibility, and urges everyone to turn themselves into virtue epistemologists (see video). His handy guide to do so:

"(i) Did I carefully consider the other person's arguments without dismissing them out of hand?

(ii) Did I interpret what the other person said in the most charitable way possible before mounting a response?

(iii) Did I seriously entertain the possibility that I may be wrong? Or am I too blinded by my own preconceptions?

(iv) Am I an expert on this matter? If not, did I consult experts, or did I just conjure my own unfounded opinion?

(v) Did I check the reliability of my own sources, or just Google whatever was convenient to throw at my interlocutor?

(vi) After having done my research, do I actually know what I'm talking about, or am I simply repeating someone else's opinion without really understanding it?"

The Atlantic / Katherine Kelaidis: What the Great Plague of Athens Can Teach Us Now

(Image: Michael Sweerts: Plague in an Ancient City / LACMA)

Katherine Kelaidis (National Hellenic Museum) looks at the parallels of the Great Plague of Athens to the current pandemic. The outbreak in 430 B.C. had a crucial impact on the Peloponnesian War that eventually ended Athenian democracy. Thucydides's account of the plague records structural and mental deficiencies familiar today, like poor housing, a lack of public health, as well as selfishness and moral weakness.

"Not that there is a right time for a pandemic, but some times are definitely the wrong one. And no time is worse than when a nation is already in crisis, when trust in its leaders and itself is already low. A time when international relations are strained and internal strife widespread. Basically, if the social and moral fiber of a society are already being tested, the widespread fear of death at the hands of an invisible killer makes everything exponentially worse."

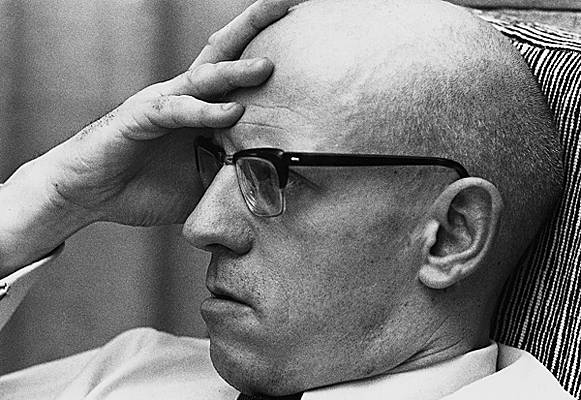

(Photo: Open Culture)

To comprehend the meaning and the gravity of the Hungarian government's decision of declaring a state of danger, one should revisit Michel Foucault's Discipline and Punish. We shared a segment from the chapter Panopticism on the OSA blog. The full text is available online.

"The constant division between the normal and the abnormal, to which every individual is subjected, brings us back to our own time, by applying the binary branding and exile of the leper to quite different objects; the existence of a whole set of techniques and institutions for measuring, supervising and correcting the abnormal brings into play the disciplinary mechanisms to which the fear of the plague gave rise. All the mechanisms of power which, even today, are disposed around the abnormal individual, to brand him and to alter him, are composed of those two forms from which they distantly derive."

foucaultblog / Philipp Sarasin: Understanding the Coronavirus Pandemic with Foucault?

(Image: Coronaviruses viewed under an electron microscope. foucaultblog / Wikimedia Commons)

Swiss historian Philipp Sarasin revisits Foucault's repeated attempts to describe modes of governing by the political responses to infectious diseases. In Foucault's writings, the specific reactions to leprosy, plague, and smallpox become models for authoritarian, disciplinary, and liberal governmentalities, which, argues Sarasin, may serve as guidance when approaching current government measures.

"[T]he smallpox model of power is essentially based on power's abandonment of the dream to completely eradicate pathogens, intruders, germs, to surveil society 'in depth,' like in times of the plague, and to discipline the movement of all individuals. Instead, power coexists with the pathogenic intruder, knows of its existence, collects data, compiles statistics, and wages 'medical campaigns' that may very well take on the character of a normation and disciplinarization of individuals."

Los Angeles Review of Books / Steven Shapin: COVID and Community

(Image: Pieter Bruegel the Elder: The Wedding Dance)

Steven Shapin, a Professor in the History of Science at Harvard University, overviews the different aspects of the pandemic; the hardship of not being able to touch and be in touch, the transformation of home (in case one has a home), the personal, social, and political nature of the crisis, and, in this context, the role of science and expertise.

"It is when threats are seen to come from outside of our society or from its margins that historians know we’ve been in this sort of place many times before. . . . Expertise warns against these presumptions, and much of our ability to mitigate the crisis depends upon the credibility of biomedical expertise. But the light of expertise is refracted through long-standing and well-entrenched attitudes about where danger comes from and who means us harm. Expert information about the virus and its travels may not be enough; expertise urgently needs to understand, and be informed by, the conditions of its credibility."

VERSO BLOG / Adam Quarshie: Solidarity in Times of Crisis

(Photo: Verso Blog)

Noting the spread of mutual aid groups immediately once the outbreak had reached Britain (see this report in Slate), Adam Quarshie summarizes the history of the idea of mutual aid, from Pyotr Kropotkin's Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution to contemporary examples of community kitchens, barter networks, and the informal distribution of food, shelter, medical care.

"The spontaneous creation of mutual aid groups is a welcome and necessary response to the crisis. But rather than merely plugging the gaps left by a state which has shirked responsibility for its most vulnerable citizens, mutual aid can offer something else: the seeds of a fundamental reimagining of our society, and the creation of social structures built on solidarity and cooperation, and which recognise our intrinsic interconnectedness. "

(Photo: POLITICO / Piero Cruciatti/AFP via Getty Images)

With regards to technology and privacy, POLITICO recounts how China, Singapore, Taiwan, and Russia reacted to the outbreak, and investigates the first proposals in European countries. Noting that the GDPR allows for divergence from the rules in matters of public interest, the article raises the question whether Europe will be able to stick to its data protection principles.

"As the outbreak in Europe worsens, the temptation to mimic such techniques will grow, testing the limits of people's attachment to privacy in a part of the world that has elevated data protection to the status of a 'fundamental right' and touts its rule book, the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), as a model for the world. . . . While a temporary relaxing of rules during an epidemic may be necessary, there are fears that changes will prelude backsliding on privacy standards."

The New York Times / Thomas Fuller: How Much Should the Public Know About Who Has the Coronavirus?

(Photo: People visit the Griffith Observatory in Los Angeles during the coronavirus pandemic. Philip Cheung for The New York Times)

According to The New York Times, "privacy appears to be winning in the coronavirus pandemic" in the US, where public health officers may be overly cautious in releasing information to the public. While Taiwan presents suspected linkages of cases, or Singapore lists affected neighborhoods or even workplaces, the distribution of information in the US is inconsistent, often lacking detailed, localized data.

“Health departments in the Bay Area make the case that releasing more granular data could heighten discrimination against certain communities where there might be clusters.” However, Glenn Cohen, an expert in bioethics at Harvard Law School argues that “If the public feels as though they are being misled or misinformed their willingness to make sacrifices—in this case social distancing—is reduced.”

C-SPAN.org / Susan Swain: Q&A with Christian McMillen on the History of Pandemics

Interview with Christian McMillen, author of the books Pandemics: A Very Short Introduction, and Discovering Tuberculosis: A Global History 1900 to the Present. McMillen talks about his research on past pandemics, and why the work of historians is important today.

"In every past pandemic from the Black Death through the plague, to cholera in the 19th century, yellow fever, etc., fear is a clear element of every single one. There has got to be a balance between informing the public in a way that makes them want to pay attention; but there's a balance of course between setting off waves of panic. In the pandemics I just mentioned, cholera, influenza, and the plague, that's been an unsuccessful balance . . . During the 1918 flu in Geat Britain, there's clear examples of suppressing information regarding the pandemic purely to not cause a secondary pandemic of fear."

Architect Magazine / Karrie Jacobs: The Architecture of Quarantine Is No longer a Thing of the Past

(Photo: The 17th-chentury lazaretto of Dubrovnik, now an arts and theater complex; Nicola Twilley)

Interview with Geoff Manaugh and Nicola Twilley, who 10 years ago started to research the quarantine as an outdated architectural phenomenon. In their forecoming book, they study the quarantines of the past to predict the quarantine of the future. In the meantime, their subject has become present-day.

"[W]e sit around and act as if there are no solutions for anything, whether it’s epidemic disease or it’s homelessness. And then all of a sudden at a flick of a switch, we’re turning either underused or abandoned buildings or temporarily unused buildings like hotels into places to house the homeless or to house people in a quarantine . . . . And I think that that kind of creative emergency thinking reveals that we already are surrounded by many spatial solutions to many existing societal problems. They’re just not possible yet politically."

The Guardian / John Vidal: "Tip of the Iceberg:" Is Our Destruction of Nature Responsible for Covid-19?

(Photo: The Guardian / Samir Tounsi/AFP/Getty Images)

Out of 335 diseases that emerged between 1960 and 2004, at least 60% percent came from animals. Increasingly, these are linked to human intervention also causing the climate catastrophy, to activities rich countries force on the Third World: the exploitation of natural resources, devastation of forests, and mining. As a result of disrupt ecosystems and destroyed natural habitats, unknown pathogens break away from former isolation. Owing to urbanisation, these spread rapidly in densely populated, often unhygienic areas.

“There’s misapprehension among scientists and the public that natural ecosystems are the source of threats to ourselves. It’s a mistake. Nature poses threats, it is true, but it’s human activities that do the real damage. The health risks in a natural environment can be made much worse when we interfere with it."

Átlátszó / Rutai Lili: A koronavírus fokozottan veszélyes a hajléktalanokra, munkaerőhiány az ellátásban

(Photo: Food, disinfectants, and vitamins bought by Budapest Bike Maffia from donations, packed in a Shelter Foundation van.)

Atlatszo.hu spoke to Zoltán Aknai (Shelter Foundation) and Zoltán Havasi (Budapest Bike Maffia) about the consequences of the outbreak on homeless people. While staying home and hygienie are not necessarily options, spring always has been a critical period to people physically and mentally weakend by testing winter months. At the same time, the pandemic forced many working in social care to stay home.

„Zoltán Aknai stressed that while people experiencing symptoms are recommended to contact doctors over the telephone and stay home, homeless people often are unable to do so. Also, setting up quarantines and isolating the ill is not possible in most of the homeless shelters."

(Front-page photo: Fortepan/Bauer Sándor)